I am a 50-plus, professional, reasonably athletic mother of three. I am currently 28 months into recovery from a serious accident that caused many injuries, including a traumatic brain injury (TBI). I am writing this blog as part of my therapy and hopefully to provide some context or helpful information to others who have been impacted in some way by something similar. Before I sustained one myself, I had little knowledge of what a brain injury (let alone a traumatic brain injury) actually meant.

“Joe Public” & the Invisible Injury

It’s my belief that “Joe Public” (i.e. the general public) has little to no understanding of brain injuries. I’m comfortable saying this because I used to *be* Joe Public. While I understood the concept that a brain could be injured, I couldn’t really have told you anything much about what that meant in practical terms.

The good and bad news is that I now have a much better (although way too personal) understanding. I think that the contrast between injuries to the brain versus injuries to the rest of the physical body is a good place to start expanding the general understanding. Physical (body) injuries are relatively easy to understand and relate to. Brain injuries are (much) harder to understand. Why is that?

Physical (non-brain) injuries – especially those to the bones or muscles or skin – are familiar. They are often visible, straight-forward to definitively diagnose, and have a healing pattern that is well understood and predictable. Almost everyone has experienced some type of non-brain injury in their life – from cuts and scrapes to strained muscles or broken bones.

Brain injuries, in contrast, are less familiar. Thankfully, our skulls do their work well – most people never experience a brain injury themselves. The injury itself is often invisible to the naked eye – because the brain is inside the skull. Seeing someone on crutches or with their arm in a sling is likely to trigger sympathy on our part, and offers to help them in ways that acknowledge their injury – like holding a door open or carrying some items for them.

If a person seems unable to remember simple instructions or struggles to fill in a standard form, then it may trigger frustration on our part. It likely does not ever occur to us that their behavior might be related to a brain injury. If we were aware of an injury then (of course) we would be more understanding. But when there’s no visible indicator like crutches or a sling, we become impatient.

Understanding Brain Injuries are More Complicated than Physical Injuries

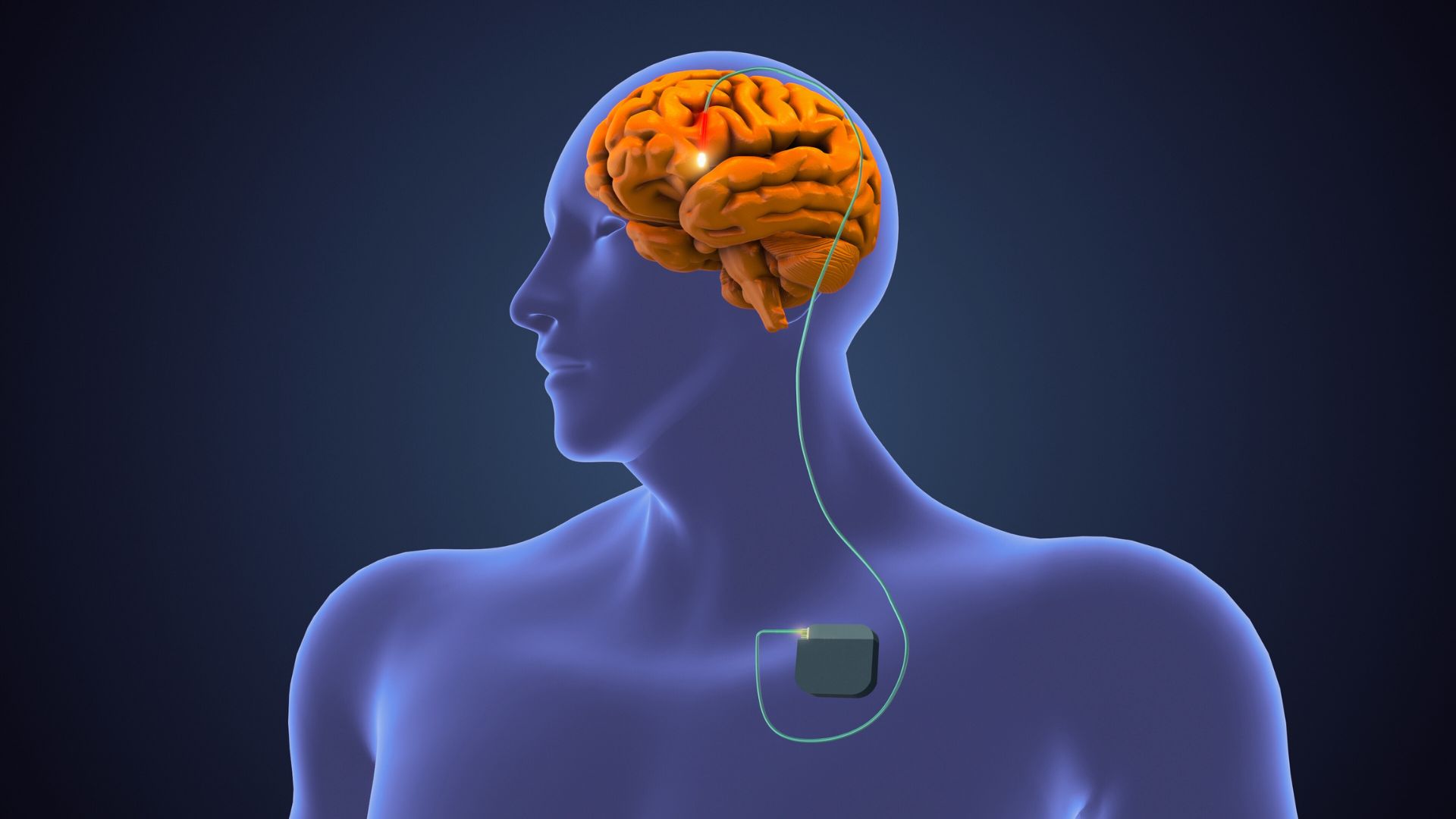

The brain is an incredibly complex organ – there are many parts or areas, each with distinct functions that contribute to the whole of an individual’s personality and intellect and functioning. A brain injury may affect a single area or multiple areas of the brain, and in varying degrees in each unique case. This makes assessing and diagnosing the impact of a brain injury often much more challenging than diagnosing a physical injury’s impact.

Most people (aka Joe Public) aren’t familiar with the working components of the brain to begin with, so trying to understand the behaviors and implications of an injured brain is an even bigger challenge. We have to learn at least a little about what is broken in order to understand how it is broken, before we can then understand different ways to try to help it heal.

The person with the brain injury may not be able to process all that information. This can make the existence and availability of therapists and caregivers, who do know what needs to be done, critically important. It is not uncommon that a person with a brain injury is unaware of the impact(s) of their injury. It is their brain, operating within its own context. The fact that it has been injured is now part of its operating context.

Think of a person who is losing their hearing and is speaking loudly (because that sounds normal to them), or someone speaking loudly after moving from a loud environment into a quiet one. In the latter case, the person coming into the quiet environment can usually quickly correct their volume by lowering their voice. However, even if or when a person with a brain injury becomes aware of their symptom(s), it does not necessarily mean that he or she will be able to correct or compensate successfully.

Understanding a Brain Injury Takes Longer to Heal Than You Think

The healing process for the brain is generally much longer than for a physical (non-brain) injury. A common expectation for traumatic brain injuries is six months to two years. Yes, years! I was stunned to learn that – and for me that learning didn’t actually happen till a good eight months into recovery.

Researchers are continuing to study and learn more about the brain, and there is potential that meaningful healing can continue over an even longer period. The healing curve will eventually plateau, but the long timeframe is especially important to remember given the invisibility of the injury and the tendency of our society to expect quick-fixes and instant gratification.

A physical injury may not be visible if the injured part of the body is not actively engaged or challenged. If you know that a person has been injured that changes your interpretation and assumptions about things. For example, if someone you know had broken their leg or had their hip replaced, and you saw them get up to answer the door when you came to visit, you would still not assume that they could run a marathon.

Similarly, having a productive, positive social interaction with a person with a brain injury does not necessarily mean that they have recovered and can be expected back at work in the near future. There may be different aspects of the brain injury that are not evident during a social conversation that still need time to heal.

If someone experienced multiple injuries at the same time, the physical (non-brain) injuries are likely to heal long before the brain injury does. My driver’s license was automatically suspended when I was admitted to the brain trauma unit after my accident. I was probably physically capable of driving a car about nine months post-accident. I was not deemed cognitively capable of even trying to drive until more than 18 months post-accident. Even then, I had to have a series of refresher lessons with an instructor before finally getting the green light to have my license re-instated so that I could drive independently.

An Injured Brain is a Damaged Brain

I believe it can be challenging for Joe Public to separate the impact(s) of a brain injury from our impression of cognitive ability. Maybe not for every Joe Public, but I think a lot of us. That challenge can lead to an element of awkwardness about how best to acknowledge or approach the topic of the injury. Just the topic of cognitive ability can be sensitive. Also, the unknown or different is, as a rule, uncomfortable. We don’t know the questions to ask and certainly don’t want to cause any offense.

As a survivor of a TBI, there was a phase where I had to work hard to get past my apprehension that things I did during my recovery might risk people thinking I was not very bright. It’s a challenge even to figure out how to articulate this, in part because of the awkwardness. I do not know what I would have thought if a friend had suffered a brain injury like I did. But I’m pretty sure that my initial reaction would have been more about lost capability rather than a damaged brain.

Be cautious of making assumptions about someone with a brain injury. The person is still the person. By definition, injury means damage. An important thing to remember is that injuries have the potential to heal, even brain injuries. There is no guarantee, but there is potential. There are recognized phases and signs that a person can progress through after a brain injury. Learning about these can provide helpful insight and information. Acknowledge your lack of familiarity with bran injuries, if that’s your reality, and ask questions whenever you can with the goal of becoming more informed.

Educate Your Brain about Brain Injuries

We know so much more about the brain now than we did just a few short years ago, but there is still so much that we do not know. I encourage you to educate yourself in any way that may be of interest or relevance to you. A better educated Joe Public will benefit all who are impacted by or involved with a brain injury and the related recovery process.

I found this book by Clinical Neuropsychologist Dr. Glen Johnson extremely insightful.

Read my previous posts in this series:

Written by